An Event Apart 2019: Inclusive, by design

/ Published:

This is a summary of my presentation that I shared at An Event Apart in 2019 in Seattle, Boston, Washington, Chicago, Denver, and San Francisco.

Let’s be really clear here though: it is difficult to represent a live talk in written format, so I hope this helps get the points across. This is the rough narrative that I use when I present this talk.

This is an exploration of inclusive design, and understanding how we can more intentionally include people with disabilities in our work as designers.

The content below is mixture of three things:

- An outline of the talk that I gave

- A visual depiction of some of the slides (including text equivalents where appropriate) that I used to present.

- The narrative that ultimately serves as my “speaking notes” for the talk.

The fine folks at An Event Apart have posted the video: Inclusive, by design. Enjoy!

Failure

I have failed. Even though I have worked with many teams on many products that have delivered successfully on the promise of accessibility, I have still failed. The failure lies not in achieving accessibility, but in how we did the work. While I worked with teams to deliver accessible products, I had not practised inclusive design to get there.

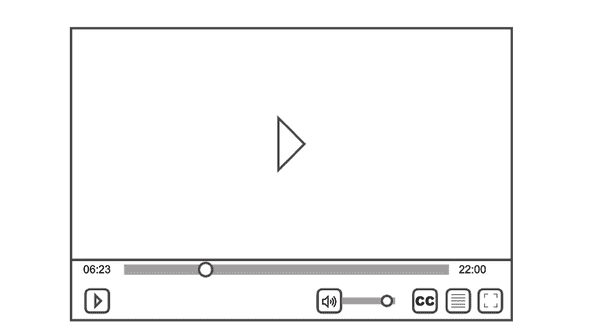

Our team created an accessible video player for a client. We did a lot of really good things when it came to accessibility. We worked iteratively in sprints. We conducted several sessions with people with disabilities during the process. We knew how to build an accessible video player.

We had assessed several other video players and knew all the things we needed to do. We also got brave and experimented with the player. We thought it might be a good idea to remove the fast forward and rewind buttons. People shouldn’t need them if the timeline scrubber was accessible, and there would be fewer controls on screen to have to work through.

So we created that, and while running usability studies and asking people to complete tasks like “Move to the 10 minute mark of the video” we ended up with feedback like this:

I couldn’t find a way to move ahead. I did try the slider, but it didn’t appear to be adjustable.

That surprised us, because we had tested it quite thoroughly. As it turns out, even though we had made the slider accessible, and did a lot of testing on it, we were coming at it from the perspective of developers and testers, and not an every day user. I believe in that case, the person was using a version of assistive technology that we hadn’t used in our testing. So our decision to remove the fast forward and rewind buttons maybe wasn’t a good one.

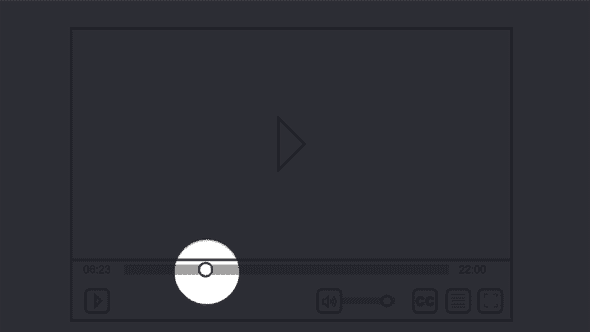

Low-vision experience

We also had feedback from someone with low-vision that ultimately noted:

I only see a small amount of the screen at a time, I couldn’t see the time counter to the left of the slider… I had to move the position dot to the right, guess how far I should go, let go of the dot, and move my mouse to the left to read the time counter

If we take a look at what this might look like for someone with low-vsion, here’s the screen.

You can see what happens if we limit the field of view while trying to move to the 10 minute mark of the video. This design doesn’t include any visual in that limited field of view that would show someone where they are in the video. The feedback that person provided should be no surprise.

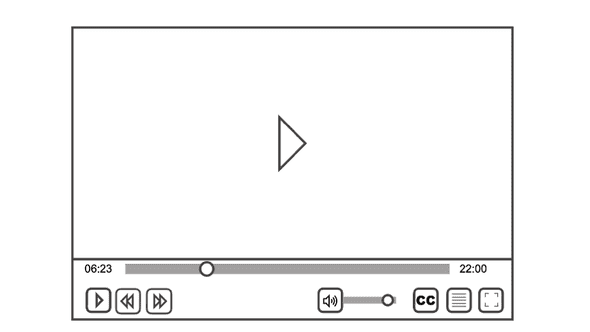

Next iteration

We made changes. We brought back the fast forward and rewind buttons based on that feedback.

We fixed things up. It wasn’t perfect. But we had better results:

It seems like the screen-reader does not want to stay within the slider bar. The buttons though, worked well.

So, yeah. It was good that we put those buttons back. It taught us an important accessibility lesson: we should provide multiple ways of doing the same thing. Two ways of doing the same thing might both be accessible, but one might be much more usable and easy to use.

Learning from real people with real disabilities

We learned a lot during that project:

- We made some invalid assumptions. We assumed that if we made the slider great, people wouldn’t need the buttons. Wrong. There were LOTS of reasons to leave the buttons in the interface.

- We delivered an accessible video player, but we definitely didn’t truly practice inclusive design.

- If we had talked with people with a variety of disabilities before we designed or built anything, I can’t even imagine what we might have come up with. Reality is, we didn’t, so we had already made almost all the decisions and were looking to the usability study for validation.

Two levels of inclusion

There are two levels of inclusion. Perhaps more, but these are the two that I think of most often when we’re talking about inclusive design.

We have inclusion in the product. In other words, disabled people can use the products that we have designed and built.

We have inclusion in the process. In other words, disabled people were actually involved in the creation of the product rather than just asked to approve at the end.

In order to ensure that we’re doing this the “right way” we need to embrace Diversity by Default.

Michael Masutha and William Rowland - both disability activists from South Africa - popularized the phrase ”Nothing about us, without us.” It was a phrase that started a movement. Here we are decades later, still trying to ensure that people can use our products, and participate in their design.

Who are we designing for?

We need to design for people not like us. We need to design for people like us. We need to redefine what “like us” actually means.

IT DOESN’T MATTER. As long as you include people with disabilites in your process. Throughout the process, not just at one stage/phase, or in one activity.

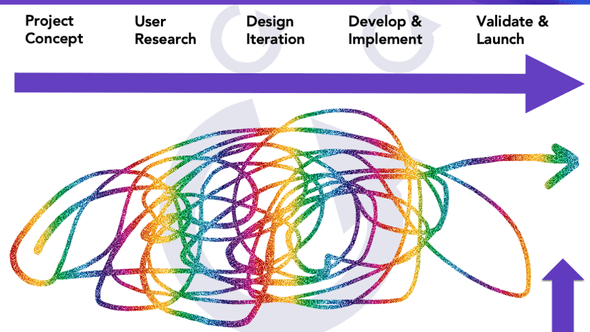

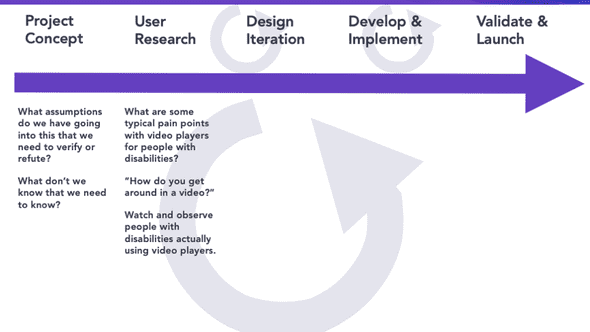

The process

What we see often is that people with disabilities are asked to come in at the end of a process to validate that we have delivered on making an accessible product. We conduct tests, we talk with disabled people. We ask them “Did we get it right? Or is it wrong?” There’s a problem with that though - we are asking disabled people to participate in the end. After we made the design decisions. After we made the implementation decisions. How did they get the opportunity to contribute their thoughts earlier in the design? They didn’t. We’ve essentially said “your value is to tell us if we did it right or wrong”

Accordingly, it is of paramount importance to acknowledge the position and the privilege we hold in the design process.

Acknowledge your privilege, your power, and your position in the design process.

We should also ask several questions that help us make our process itself more engaging and helpful. We can ask:

- How might we engage people with disabilities earlier in the process in a more meaningful way?

- How might we empower people with disabilities to take the role of and contribute as a co-designer?

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge a few things here today:

- I hold most of the power in the design relationship between me and people with various disabilities. My greatest power is to give that power away.

- My lens on inclusive design is based on the work I’ve been doing for 21 years: making the web a better place for people with disabilities.

- There are other lenses of inclusion. We often think of diversity as it relates to race or gender/gender identity or sometimes even age. We don’t often hear disability called out. The lens I have on inclusion is not more important than or better than the other lenses. They are just different. And equally valid.

- I’m a white, Canadian, cis-het male in his late forties, and I have no disabilities that have resulted in discrimination or exclusion… at least not yet.

Revisiting the video player

Had we been practicing inclusive design rather than creating an accesible video player, we might have done things differently. In early phases as we were getting going, we would have asked and explored questions:

- What assumptions do we have going into this project that we need to verify or refute?

- What don’t we know that we need to know?

- What are some typical pain points with video players for people with disabilities?

- How do you get around in a video?

- Watch and observe people with disabilities actually using video players.

- What problems are people trying to solve? What are the opportunities for us to innovate?

Had we done that, we might have solved the low-vision issue right away. We might have known that many people rely on the fast forward and rewind buttons to get around in a video, and we would likely never have tried to remove them.

When we’re doing testing at the end of a cycle or at the end of a project, we’re working with people with disabilites in the solution space. When we ask questions up front, and engage disabled people as co-designers, we are working with them in the problem space.

Spend more time including people with disabilities exploring the problem space instead of the solution space.

Who is doing this well?

I usually point to these as great examples of inclusive design:

Lessons learned

From all of this, there are important lessons to learn.

- Start earlier

- We know less than we think

- Other people know more than we think

Inclusive design, in practice

To put inclusive design into practice, we need to take some steps to start exploring the problem space. How might we make a game like Twister more accessible to people with different disabilities?

We can come up with lots of ideas on our own as designers. But that’s mostly inclusive design thinking. Why? Because we weren’t working with people with disabilities during that ideation process — we were just coming up with ideas about what we THINK people with disabilities might need. Of course, there are many disabled designers that will do a great job of representing their disabilities and perhaps those of others in the design process and that ideation period. However, even if that is that case, it is very hard for a designer to have the lived experience of people with a wide variety of disabilities. We need to tap into the lived experience of people with the disabilities that we want to serve.

To turn that thinking into inclusive design doing, we need to approach this the way we have talked about it above. Exploration of the problem space, not just the solution space, and not just via our own conjecture and false empathy.

Moving from thinking to doing

In order to move from inclusive design thinking to doing, we need to dig in, and we need to find ways to invite people with disabilities into our process so that they can participate.

Identifying systemic exclusion

When I confront people with the concepts of inclusion and exclusion I often hear this familiar refrain:

But Derek, we aren’t excluding people intentionally.

And my response is always:

Yes, but you’re not including them intentionally, either.

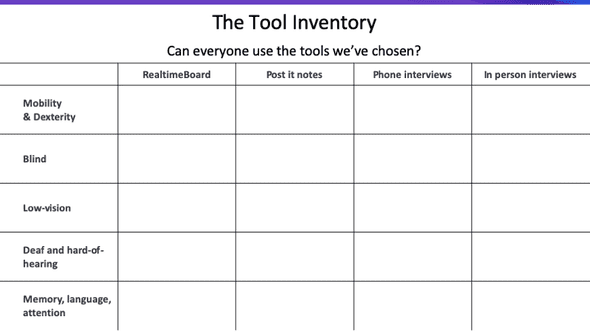

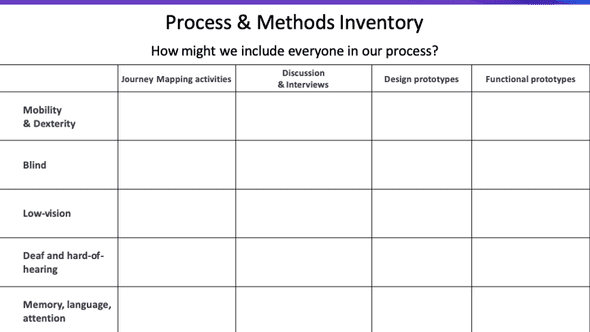

This is the basis that we use for identifying systems that exlude people. This exclusion might be hidden, and it might be based in our brains. Or… it might just be there because of the tools and the methodologies that we’ve chosen to employ in our design process.

To help identify this type of exclusion, we often use a tool and methodology inventory that might look something like this:

What next?

We should always be looking to improve. That means asking questions like “Based on the last project, how might we improve our process to be more inclusive?”

And we can strive to meet all of these goals for inclusion:

- Agency You should have the ability and opportunity to participate in solutions that you will use, and that will impact your life.

- Belonging / Othering Your participation should be predicated on using the same tools, at the same time, in the same space, using the same process as anyone, to the greatest extent possible.

- Value Your participation in a process is valued rather than tolerated or accommodated.

If we can look at these goals as part of something bigger… as part of something more than just making accessible products that everyone can use… we’ll actually start to get somewhere. Because when we have the choice between solution A and solution B, we should choose the solutions that help achieve the goals of agency, belonging, and value.